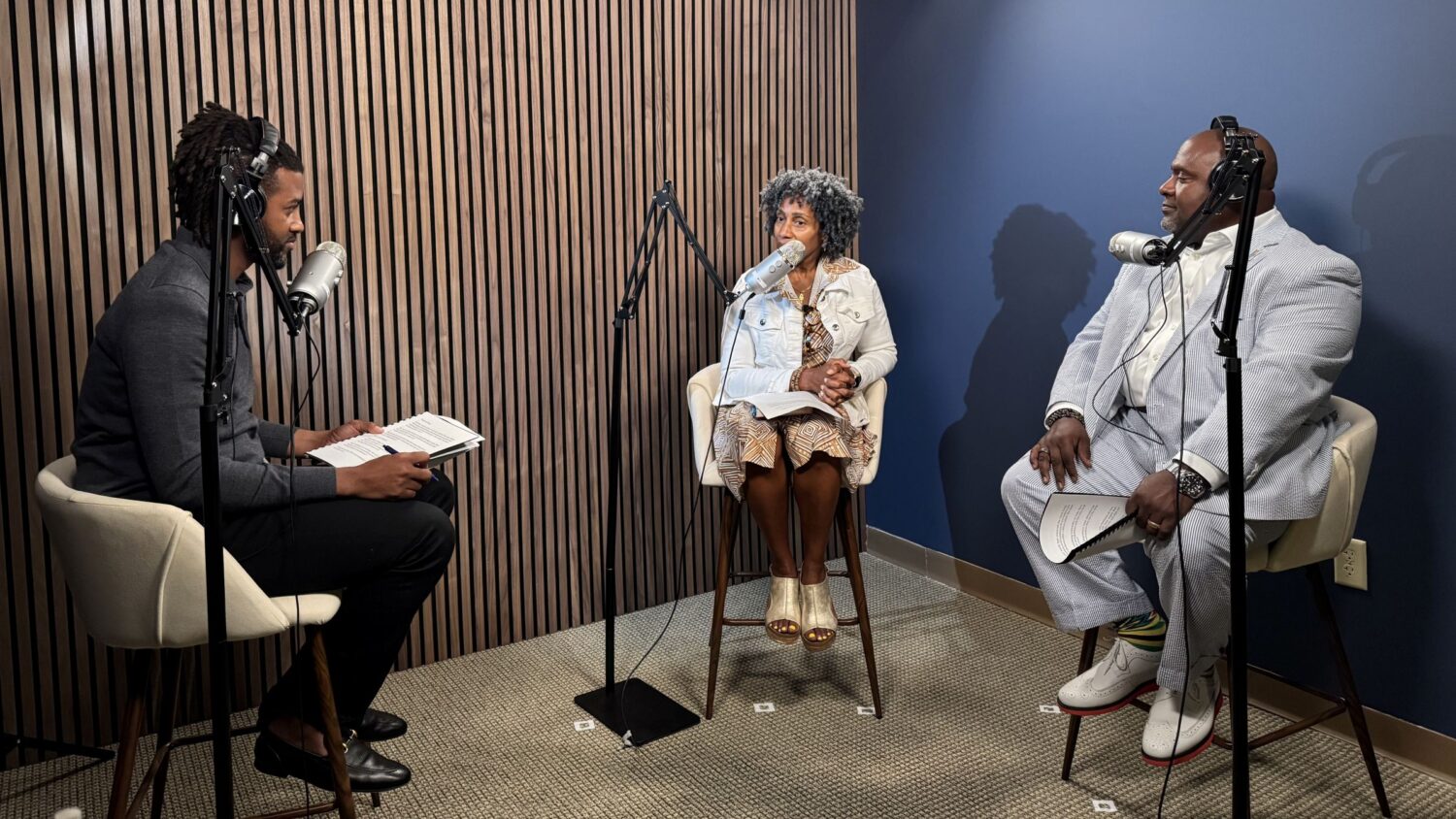

In this episode of the podcast, Isaiah Oliver joins two national leaders whose work has shaped philanthropy at every level—from grassroots communities in the rural South to the largest philanthropic institutions in the country. Dr. Sherece West-Scantlebury is president of the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation in Arkansas, after previously leading the Foundation for Louisiana and serving at the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Her husband, Joe Scantlebury, began his career as a lawyer from Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, and went on to serve in senior philanthropic leadership at the Gates Foundation and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. He is now the president of Living Cities, which brings together some of the most influential philanthropic and financial institutions in America—MacArthur, Kellogg, Robert Wood Johnson, M&T Bank, and Truist.

Below is a transcript of the conversation.

Isaiah Oliver: Thank you so much, Dr. Sherece and Joe, for being with us today.

Guests: Thank you for having us.

Isaiah Oliver: I’m going to open up right away—we’re going to dive in here. Both of you have walked very different but complementary paths into philanthropy. What experiences from your childhood or early careers most shaped how you lead today? We’ll start with you, Dr. Sherece.

Dr. West-Scantlebury: I grew up in the Murphy Homes in Baltimore. It was a public-housing community—or was; it’s actually HOPE VI, where those policy wonks tore down the Murphy Homes some years ago. But I grew up there, and even in those early formative years—6 to 10 years old—I knew that something just wasn’t right about this community.

By “right,” I mean the level of violence, the physical environment. It wasn’t a pretty place—aesthetically. Just being there, I knew, some kind of way, this is not right. But I didn’t know “structural racism” at six. I didn’t know anything about community development. I didn’t know anything about redlining. I knew none of those terms or what they meant. Looking back, I realize I was living all of that policy when I was living in the Murphy Homes.

So the question was: How do you change a community like the Murphy Homes into a positive place for kids and families to grow and thrive? Later, once I got educated and could put the words together, that became my question and my quest. My career has led me to try to answer it. I don’t have the ultimate answer, but I’ve been blessed—over 30 years in philanthropy—to understand how private philanthropic resources play a role in community transformation. For me, it was that question: How do I make this community better? How could this be better? That question drove my career and led me to philanthropy.

Isaiah Oliver: And you, Joe?

Joe Scantlebury: So I’ll start where Sherece left off. I’m the son of two immigrants who eloped from Colón, Panama, and decided they were going to make it big in the United States together. They were very romantic and very young. It didn’t quite work out the way they thought—divorce and separation—and before I knew it, I was being raised by a single mom.

As a single mom in Brooklyn, it was tough going for a new person in the country. So she sent me to live with my grandparents in Colón, Panama, and there I was nurtured by folks who had lived in Panama under American segregation, who had lived through storms and challenges—but at the end of the day, they were always about advancing and believing that they could.

When I returned at six years old to start school in the U.S., I went to P.S. 3—Bedford. Ultimately, my mother had to put me on New York City public transportation to get back and forth to school once we left the neighborhood and moved to Crown Heights. I’m sharing this because, throughout that time—grade school, high school, college, and beyond—there were always people who said, “Keep striving on.” There was a community of folks who believed that I and other people like me could make it, should make it, and keep advancing.

So that sense of community—even though these were strangers who saw me in my school uniform lugging a bunch of books, rooting for me, “Young brother, keep going!”—I didn’t know who they were, but it kept me in stride going forward. How I got to philanthropy is a longer story, but I’ll simply say this: that sense of community, that sense of belonging, that sense of knowing that—even without all the good or all the fair things—we can still strive ahead with the community around us.

Isaiah Oliver: So Joe, Living Cities convenes some of the most powerful funders in the country. What do you see at that table that’s relevant for communities like ours?

Joe Scantlebury: Sure. I see philanthropic leaders who are clear that they’re better together than apart—that’s first. I see leaders who can face racial equity as an issue without having to, what do they call it, “signify” around it. In other words – let’s address the data, let’s address where the inequities are, let’s address where the systems aren’t working—and then let’s be clear about how we do that together.

They also look to us to innovate and try new things—sometimes fail—but to share the knowledge, both of their individual efforts and their collective efforts, so those things can be replicated with public and civic leaders, and, more importantly, so that capital can follow solutions.

Right now we’re very much focused on capital. How do we build social capital—bringing people together? How do we share knowledge capital—the things that philanthropy has already invested in, has knowledge about, but that sometimes sit in an archive, on a shelf, or on a website, and aren’t made useful for folks who are asking the very same questions that were solved in 1995? We’re still having the same conversation today.

And finally, how do you actually separate the prevalence of race and risk when it comes to capital investment? We can invest in cities—we have seen cities and places rise and housing be developed—but very often it doesn’t include the people who were calling for that same housing a decade earlier. How do we really problem-solve around the needs of the whole, because we live in proximity and no one’s going anywhere—we’re all going to be together. How do we build together and build the economy we deserve—one that’s inclusive, equitable, prosperous, and thriving? At Living Cities, we believe everyone in American cities is entitled to an economically sustainable life: an ability to thrive, to build wealth, to be connected, and, more importantly, to see into the next generation and know that you’re not left out—much like I wasn’t as a kid.

I’ll say, in the spirit of living in American cities—Dr. Sherece, your work has taken you from Baltimore to Detroit, Denver, Baton Rouge, across the rural South, and in Arkansas. What lessons from those places are most transferable to a city like Jacksonville—often called the most Northern Southern city?

Dr. West-Scantlebury: Looking at other places outside of Jacksonville, you see nothing but similarities. When a decision is made—usually a policy decision by leaders of an area—not to invest in a community, for whatever reasons—whether it’s intentional redlining or otherwise—there are communities that historically have not been invested in. Most times that’s based on race; often, if not race, then income, because there are very low-income white communities as well as Black and Brown communities.

When the decision is made not to invest, you get similar—if not the same—outcomes: people who are disaffected; education outcomes that aren’t on par with peers in other parts of the state or more affluent areas; reading scores that aren’t on par; maternal-child health outcomes that aren’t on par. It’s pretty much the same—when you don’t invest, you get spillover effects.

That’s not to take away from what’s unique and special about Jacksonville, but wherever you go in this country—and beyond—the decision not to invest results, most times, in negative outcomes. The policy challenges are how to deal with those outcomes, how to disrupt the systems that serve them, and how to hold the power structure accountable for ensuring those outcomes change. That may differ by community—some have city councils, strong mayors, weak mayors, etc. Structurally it may be different, but it’s the same thing: How do systems—foster care, maternal-child health, education, transportation, health care—work effectively in these communities? How do we get those systems to do so? That’s what we need to break through and figure out.

Isaiah Oliver: You’ve been leveraging the power of philanthropy for 34 years, anchored in two decades of work at the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation. What are the most important ways philanthropy can show up authentically in communities with deep legacies of inequity?

Dr. West-Scantlebury: For philanthropy to show up authentically, it requires listening, but it also requires risk and boldness. Doing the same type of grantmaking over and over—funding short-term, restricted programs—won’t change results for these communities. At this stage, it requires sustained, significant partnership with philanthropy. It requires grantmaking focused on systemic change, not a charity, program-by-program approach to supporting what communities say they need.

It requires design thinking and innovation. It requires stepping out of our comfort zones and figuring out how we reorganize systems to serve these communities better. It requires these communities having a voice—and being educated about those systems—to know what to demand, and it requires those systems to be willing to listen and change.

Systems rarely disrupt themselves; they often need outside agitation. Now, when I say that, some may think I’m talking about demonstrations or marches—and maybe it is that—but that’s not what I mean. I mean, if data show that kids entering foster care come mainly from particular communities, that means a specific intervention needs to happen—and we must be willing to call it what it is and innovate the interventions needed to stop the flow.

If we find that kids aren’t reading on grade level—especially boys, and boys of color—and school systems say, “Everybody’s the same; we treat them all the same,” that means it isn’t working. Something different needs to occur. First, you need the courage to say something different needs to occur—not to blame those kids or their parents. What intervention would be most effective so they begin to read on grade level with everyone else?

It requires courage and boldness to say, “We have a challenge; we want to address it; here’s what we’re going to do; here’s the role philanthropy can play.” Often philanthropy’s role is innovation, experimentation, out-of-the-box thinking, risk—funding the wild idea that government money may not.

One example from my time at the Annie E. Casey Foundation: a system introduced comic books into schools. Boys like comic books—no surprise. If they’ll read a comic book, let them read the comic book, because the goal is for them to read. If they don’t like Dr. Seuss, give them the comic book. These weren’t frivolous; they were curriculum-based, phonics-based, and it was working. Then someone outside the system had a problem with comic books instead of “regular” books, and they had to stop the intervention—despite it working and boys starting to read on grade level.

That’s what’s required: out-of-the-box, “crazy” thinking—and philanthropy getting behind it. If you need a tried-and-true, proven approach before you start, you’re not doing philanthropy—you’re being safe. Philanthropy should instigate what happens in systems.

Isaiah Oliver: We know power exists across sectors and systems. Joe, your work is about bringing a multi-sector approach to deep community problems. But many institutions are now retreating from explicit racial-equity language. How do you stay anchored in the truth while still building coalitions across difference?

Joe Scantlebury: The retreat from racial-equity language is understandable in an environment with explicit hostility to even talking about race. Unfortunately, some of that is born of fear. By 2045, this country—like it or not—will be a predominantly multiethnic, multiracial society. People ask, “Do I get erased?” No. You’re part of the tapestry. You’re part of the whole history—some of which you haven’t been willing to learn from, be part of, or acknowledge.

When I was in grade school—and I’m not that much older than Charisse—the only Black people you ever heard of were George Washington Carver, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and Martin Luther King Jr. There were no other Black people at all—none who weren’t described as slaves. It took intentional effort from people outside the school system to introduce history that was always there but not acknowledged.

The challenge with that lack of acknowledgment is that you miss opportunities to build new coalitions, new partners, and new ways of being. You stop understanding what’s happening around you: “Why are these people living the way they are?” You don’t have the eyes to see potential innovations.

In our work, where this really runs afoul isn’t about whether words get said, but whether I can see well enough to invest in people. There is no growth, no return, without investment—period. You see evidence of investment in all the places that rise and all the places that fall—everywhere, even internationally.

The question for us is: Can we see people we might hold in contempt or stereotype as worthy of investment? If I don’t trust, like, respect, or understand you, I’m not willing to invest—even if you’re innovative or profitable. I have to take the time to understand and affirm your humanity if I’m going to invest public, private, or philanthropic dollars.

So our work is about closing the distance between communities and people—public, private, and civic leaders—so you don’t have to call it “racial equity,” but you see me, and you understand I’m worthy of investment. If I can see your talent, creativity, and ingenuity, then you can help grow this economy.

For those who can’t see me: I’m hair-challenged as a 63-year-old man. But imagine if I had understood Black women’s natural hair-care products ten years ago—I’d be a millionaire. Imagine when we “discovered” guacamole—once only in Mexican restaurants, now everywhere. If I had heard about that 20 years earlier and invested in that Mexican creation—man, I’d be a millionaire.

There are so many common things we all enjoy that, if I can see you, I can invest in you. But if I refuse to get beyond my limited understanding of your history and story, I can’t see you—and I can’t invest—so we can’t grow.

Isaiah Oliver: What do you see as the biggest opportunities and risks for community-building organizations in this moment of deep division?

Bring us together. Invest in common tables and common conversations. Don’t be afraid of the narratives we hold about each other—push past them. What do we want to do together? Okay, you think I’m this way; I think you’re that way. What does our city need? We’ll disagree and debate, but we’ll stay at the table. Philanthropy has to create that container so we can talk about the enabling environment policy should bring for sustained investment to build what we need.

We have to challenge each other’s perceptions—and still have dinner. We have to debate—and still see each other. We have to tell the stories of our children because, as quiet as it’s kept, a lot of white people are struggling. Affordability is an issue in every city. Income inequality is everywhere. People are worried about investments, retirement, health care, families. While we ignore those issues, we’re distracted by rhetoric and noise, rather than building what we need—an economy that works for all, period.

Dr. West-Scantlebury: But we’ve created a moment of scarcity—and made it worse.

Absolutely. In this hostile environment—hostile against nonprofits, against all things equity—the pullback of federal dollars means fewer dollars to states to do the work their systems are intended to do. Philanthropy, as you mentioned, is retreating. We’ve created even more scarcity. We were already operating out of scarcity; now it’s hostility, fear, and scarcity.

So the question—one I don’t have a full answer for—is: How do we use this moment as a moment of opportunity within this perceived scarcity?

Isaiah Oliver: I’ll let you close us out with this: What’s at stake for philanthropy and for democracy if we fail to meet this moment?

Dr. West-Scantlebury: If we fail to meet this moment, there will be a lot of good lessons on how to meet it next time. Sometimes you have to fail to go forward; you have to fall flat on your face before you know what adjustments to make to succeed. I am not advocating for the bottom to fall out, but as a principle, sometimes you have to fail to learn.

I’d also say: look for opportunities to use the resources we have—better and differently. I’m not saying it’s enough; most will tell you it’s not. We don’t have enough for school funding, maternal and child health care, early childhood, and more. I’m not disagreeing. But in this moment—when it doesn’t look like new resources are coming—it’s time to look at systems, at how things are done, and ask how we can make what we have work better.

Also, for philanthropy in particular—this is not the moment to retreat. If your mission is to get dollars out, reserving your coffers is not the approach. I’m not saying deplete them. Philanthropy cannot, under any circumstances, make up for government—can’t do it, doesn’t have the money, nor should it.

However, philanthropy can bring strategy and innovation—different ways of doing things—funding disruptors who can change systems so they function better through solutions-oriented approaches. That’s where we should invest our time and energy in this moment of scarcity: learning to use the resources we have better and figuring out how to generate resources that will carry us into a different future.

Isaiah Oliver: Dr. Sherece West-Scantlebury, Joe Scantlebury—thank you so much for joining us today. I look forward to continuing the conversation tonight at our Donors Forum.

Guests: Thank you so much.

Forever Forward is a podcast created by The Community Foundation. You can find our podcast on many popular podcast platforms, including the Podcasts app for Apple and Google podcasts app. You can also find the podcast episodes here on our blog, and listen directly from your browser. However you like to be informed, we hope you enjoy listening.

Questions? Email Stephanie Garry Garfunkel at sgarfunkel@jaxcf.org for help.